Why putting your eggs in different baskets makes sense

To me the main aim of investing is very straightforward. It is to grow the buying power of your money.

Put simply, you want the money that you invest today to buy you more things in the future. If you want to have enough money to eventually stop working and retire in some form of comfort this is the goal you should be aiming for.

Phil Oakley's debut book - out now!

Phil shares his investment approach in his new book How to Pick Quality Shares. If you've enjoyed his weekly articles, newsletters and Step-by-Step Guide to Stock Analysis, this book is for you.

Share this article with your friends and colleagues:

Beating the enemy of inflation

To do this, the value of your investment portfolio has to grow by more than the change in the cost of living - it has to grow faster than inflation. Inflation is your number one enemy. Even with 2% inflation, you will need nearly £150 in twenty years time to buy the same amount of stuff that £100 buys today.

It would be nice if you could achieve this goal by just put your money in a savings account every month and forget about it. A prolonged bull market in shares would also be helpful. But in a world of low interest rates, fairly high share prices and uncertainty about future economic growth, meeting your goal is probably going to be quite tough.

To get there you are probably going to have to take some risks with your money.

Sticking your money in a building society account or buying lots of government bonds is not going to get you very far given the current interest rates on offer. You might be alright if you are able to save lots of money.

This is why lots of people have turned to the stock market in recent years. It's one of the few places where there's a chance of getting a decent return on your money.

Coping with the stock market roller coaster

However, that possibility comes with the risks of a roller coaster ride of the ups and downs in share prices. Lots of people struggle to cope with this.

They can't cope with seeing the value of their savings pots fall a long way and often sell their shares when this happens and seek the safety of cash and bonds. They think that shares are just too risky.

Unfortunately this kind of behaviour means they lose their focus on achieving their investment goals - having enough money to retire on. It's because they don't understand the difference between risk and volatility.

What do we mean by risk?

To most people investment risk is about losing money. That's how I see it too.

But for me the risk is not having enough money when I need it. It's about losing money forever without any chance of getting it back. For someone saving for retirement that risk might be in 10, 20 or 30 years' time, not the value of your portfolio today.

The regular ups and downs of the stock market which change the value of your portfolio is known as volatility. Volatility is not the same as the risk of losing money or falling short of your goal.

Volatility measures how much the value of your savings pot moves up and down over a period of time. It is measured by calculating the standard deviation of returns which tells you how far they have moved from their average values. The bigger the standard deviation, the more volatile an investment has been. Shares tend to be very volatile investments.

Big gains in share prices make us feel good, but big falls - especially ones that occur just before we need our money - can be disastrous. High levels of volatility can also play havoc with our emotions which makes it more likely for us to make mistakes such as chasing things that have already gone up a lot and selling things that have gone down - a proven way to investment mediocrity or worse.

Over a long period of investing - say 20 or 30 years - volatility becomes less of an issue. That's because there is more time for good years in the stock market to offset bad years. The closer you are to needing your money - such as retirement - the more attention you need to pay to the potential volatility of your investments.

This is why people tend to shift their money out of volatile shares into less volatile investments such as bonds as they get nearer to retirement. This makes sense as you don't have enough time to recover from a big fall in the value of shares just before retirement

If you don't like the ups and downs that come with stock market investing there is something you can do about it. There is a way to get reasonable investment results whilst keeping volatility manageable. It's called asset allocation and is arguably one of the most important lessons an investor can learn - especially if you like to sleep well at night.

Asset allocation explained

The best way to reduce volatility is to spread your money across lots of different investments. This is known as diversification or not having all your eggs in one basket.

Having all your eggs in one basket - or having all your money in one particular investment - can be very risky. You might make a fortune or lose everything. So instead of owning just one share you can reduce your risk by owning a fund with lots of shares.

Asset allocation is like having lots of eggs in lots of different baskets. Each basket represents a different type of investment which behaves in a slightly different way to the other baskets.

These imaginary baskets are made up of investments such as shares, bonds, cash, property, precious metals and commodities. They produce different investment returns with different amounts of volatility (see below) depending on what's going on in the world. For example, shares and property do well in times of modest inflation, bonds and cash are better for times of recession.

By having some of your money in a different basket you might still be able to achieve reasonable returns but significantly reduce your volatility compared with having all your money in the stock market.

What's good about asset allocation is that you can decide how much you want to have in each basket depending on how long you are investing for and/or how much risk you can cope with. So a younger investor saving for a long time can afford to have more money in shares because hopefully there is enough time for good years to offset the bad ones. Whereas someone close to retirement or who doesn't like risk would have more money in bonds and cash.

How asset allocation works

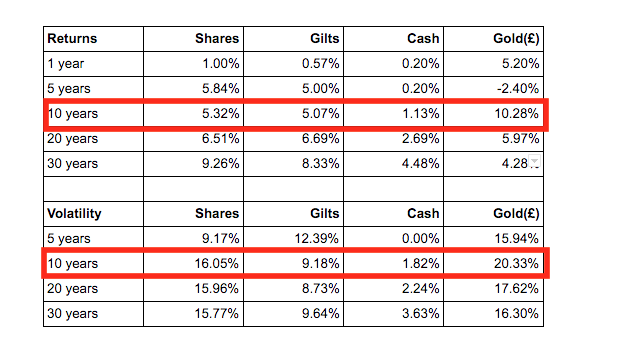

In the table below, you can see the average returns and volatility for UK shares, UK gilts, cash and gold between 1983 and 2015. Asset allocation is all about trying to match your investment goals (the required returns from your portfolio) against how much volatility you want to put up with.

Average annual investment returns and volatility 1983-2015

| Asset | Avg Return | Volatility (SD) | Good year | Bad year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shares | 10.23% | 15.83% | 26.06% | -5.60% |

| Bonds | 8.36% | 9.27% | 17.63% | -0.91% |

| Cash | 4.84% | 3.83% | 8.67% | 1.01% |

| Gold | 3.51% | 16.06% | 19.57% | -12.55% |

Source: Barclays Equity Gilt Study, Goldprice.org, FTSE, iShares.

Good year and bad year refers to the range of expected returns 2/3rds of the time or one standard deviation.

Bear in mind that what has happened in the past won't necessarily be the same as what happens in the future.

Historically you have received higher returns from shares but they have been more volatile (their returns have had higher standard deviation and bounce around more). Government bonds and cash have produced lower returns but with a less volatility. Gold - a supposed hedge against really bad things happening - has given low returns but with lots of volatility. In fact, since 1983, gold has been more volatile than shares and has made less money than cash in the bank.

The returns and volatility from different periods are shown in the table below

Over time shares and gold have been consistently more volatile than cash and bonds.

Correlations between different financial assets

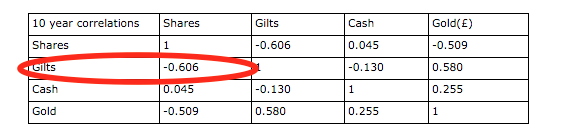

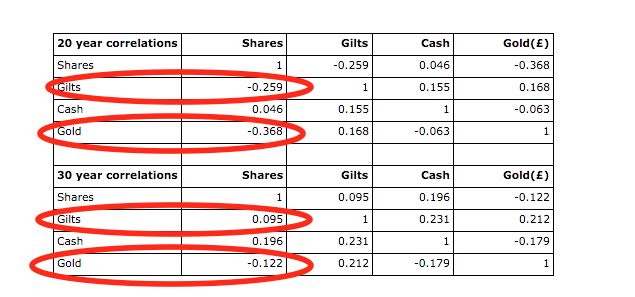

What you can also see is that the returns of different assets also behave differently to each other. We can find out how by looking at how much the returns of different assets move together - how correlated they are.

By spreading your money across assets that aren't strongly correlated with each other you can protect your portfolio from some of the big ups and downs that come from having all your money invested in shares.

Correlations can change over time depending on what's going on in the world. Say you are looking to protect yourself from a stock market crash. In this case you would want to own an asset that goes up when the stock market goes down; something that is negatively correlated with shares.

Here you can see that during the last ten years, the returns from UK gilts have had a fairly strong negative correlation with UK shares as have the returns from gold - they have moved differently to shares. When shares have had good years they have had tended to have bad years and vice versa.

The return from cash has had virtually no correlation with the returns from shares. Over 20 years and 30 years the correlations are weaker. Over 30 years, the returns from gilts are very slightly positively correlated with the returns from shares which still suggests that they have been a reasonable hedge against a falling stock market.

Bear in mind that at some times - such as the financial crisis in 2008 - different assets can become highly correlated with each other and all move in the same direction. Only cash seems to behave the same.

Asset allocation in practice - Harry Browne's Permanent Portfolio

One of the simplest examples of an asset allocation strategy is an approach developed by US financial advisor Harry Browne in the 1970s.

After living through the terrible investment markets of the 1970s, Browne set about devising a strategy that was intended to be simple, safe and stable. He wanted to put together a portfolio that could cope with most of the things that the world could throw at it - recessions, inflation, deflation - as well as making reasonable money when times were good.

What he came up with was a very simple portfolio which was invested in the following way:

- 25% in US stocks

- 25% in US Treasury bonds

- 25% in cash

- 25% in gold

Browne believed that investing in just these four assets would help most investors achieve their goals with a lot less worry. He reckoned that an event that damaged one part of the portfolio would be good for one or more of the other parts of it. Also, because each investment only accounted for 25% of the total portfolio, anything bad that happened to one part of it would not devastate the whole plan.

This portfolio became known as "the permanent portfolio". Browne wrote about it in a book called Fail-Safe Investing: Lifelong Financial Security in 30 minutes.

According to Browne, an investment in shares would provide good returns when times were good. Bonds also tend to do reasonably well when the economy is calm and growing steadily. Recessions or periods of deflation (falling prices) were bad for shares but good for high quality bonds and cash because the buying power of these investments increased. Periods of high inflation, whilst being bad for bonds, were good for gold.

Not only was the portfolio simple in theory it was also simple to run too. At the start of every year the investor would start off with their portfolio spread equally across the four different investments. At the end of the year, the portfolio would be rebalanced back to equal weightings (25% in each investment).

Annual rebalancing is the closest thing to a free lunch in investing. By doing this it means that you automatically sell a bit of the investments that have gone up and reinvest the money back into the ones that have done less well. So you are selling high and buying low whereas many investors do the exact opposite. Studies show that rebalancing is a good way to boost the returns of your portfolio whilst reducing risks at the same time.

This approach is quite simple but does it work?

According to authors Craig Rowland and JM Lawson in their book about Browne's permanent portfolio, between 1972 and 2011 a portfolio like this, rebalanced annually, delivered annual returns of 9.5% compared to 8.8% from the one that was left alone. It also increased the buying power of your money by generating annual returns 4.9% more than inflation.

That might not seem much. But over 39 years, the rebalanced portfolio only lost money in four years with a biggest annual loss of 4.9%. The other portfolio lost money in eleven years with a biggest loss of 21.6% - which portfolio would you rather own?

The Permanent Portfolio in the UK

I've taken a look at how a permanent portfolio approach would have fared in the UK over 10, 20 and 30 years and compared its performance with an all share portfolio. I've also compared it with a very simple portfolio divided equally between shares and government bonds which is rebalanced once a year.

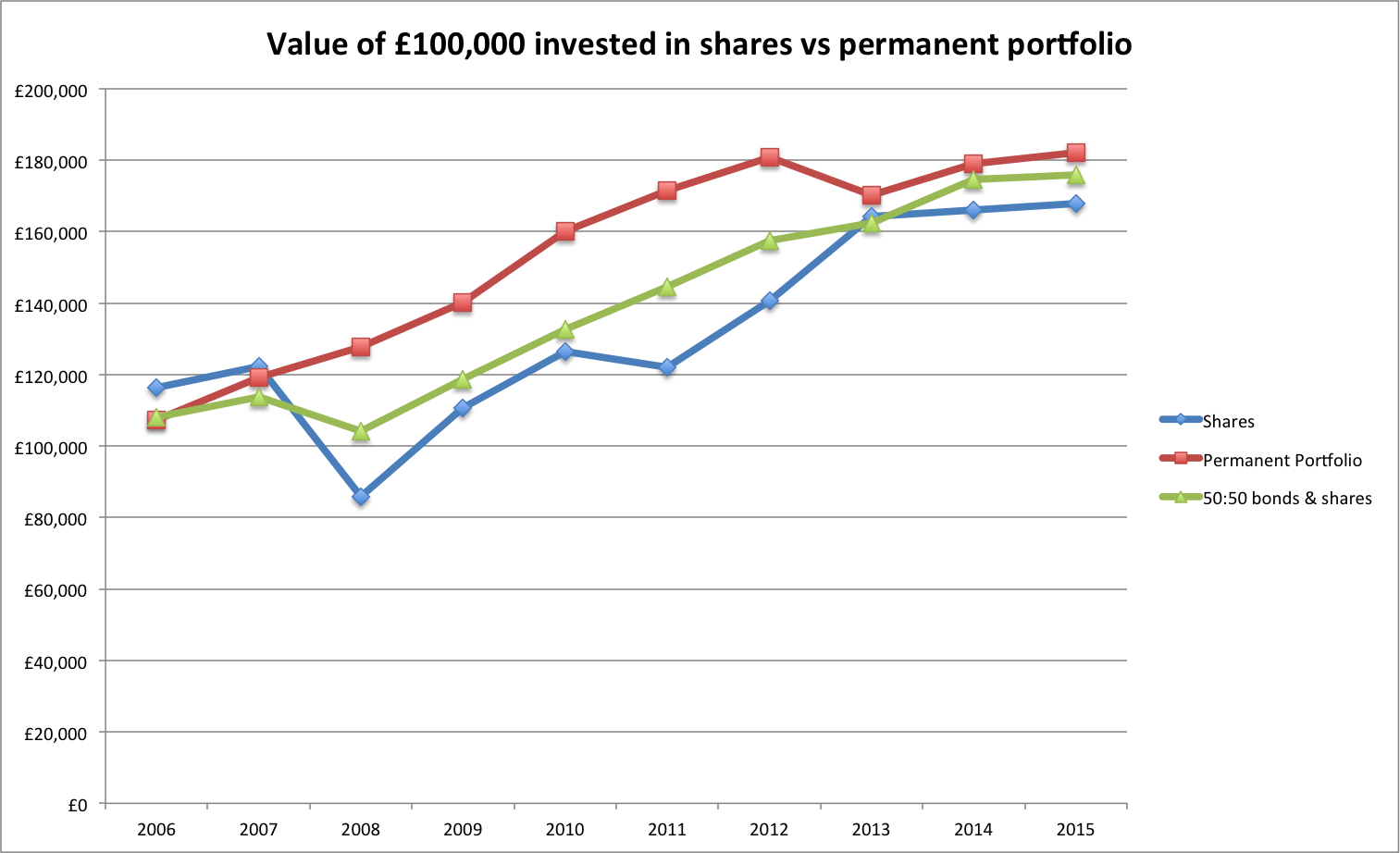

During the last ten years this simple asset allocation portfolio has performed better than a portfolio of shares and with a lot less volatility. It also performed slightly better than the 50:50 portfolio with slightly less volatility. The permanent portfolio only lost money in one year as did the 50:50 portfolio.

| 10 years | Average Return | Volatility | No of losing years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shares | 5.32% | 16.05% | 2 |

| Permanent Portfolio | 6.17% | 5.49% | 1 |

| 50:50 bonds & shares | 5.81% | 6.39% | 1 |

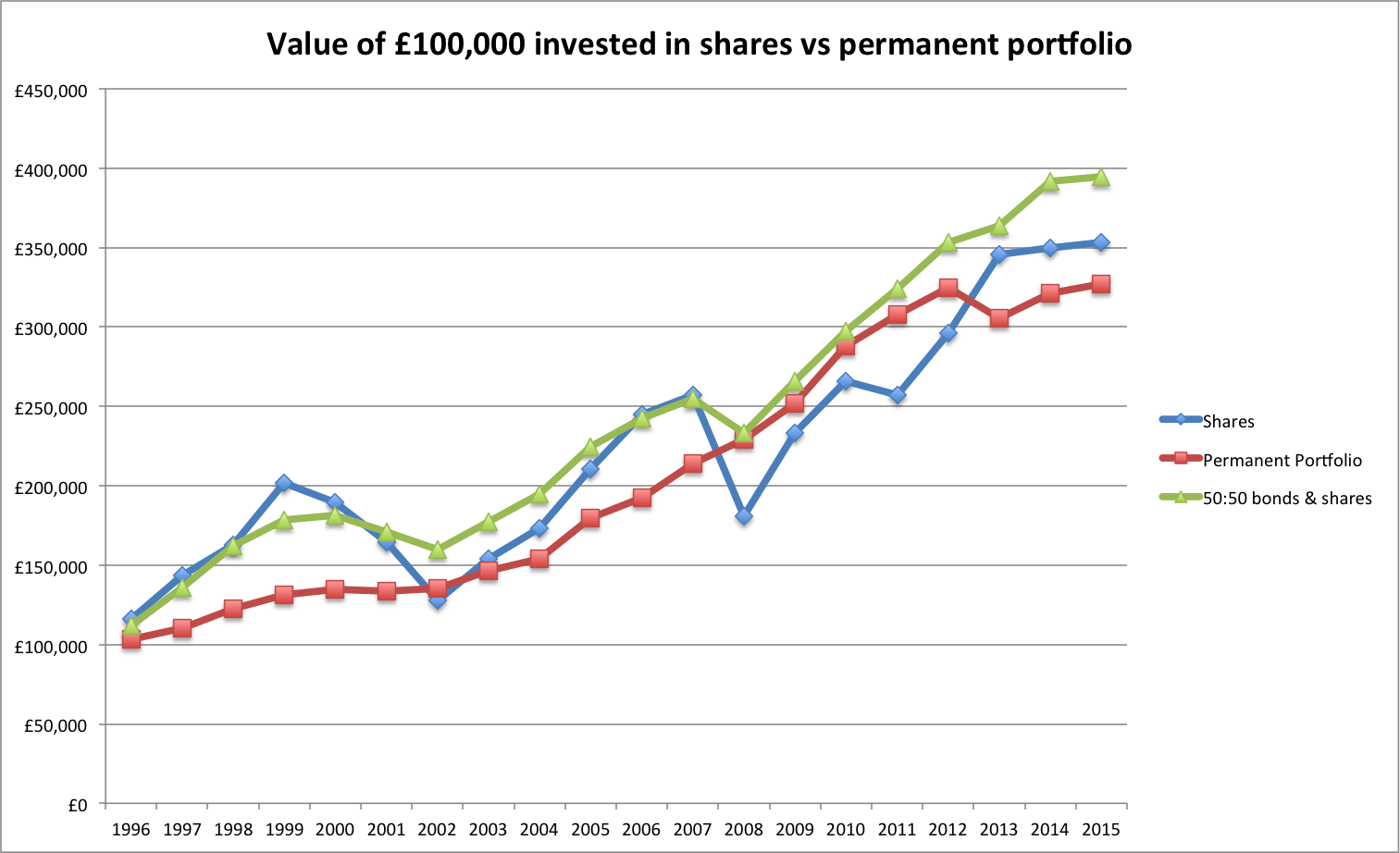

See the chart below for a comparison over 20 years. Shares have performed slightly better but have been a lot more volatile than the permanent portfolio and with more losing years. The 50:50 portfolio was the best performer with around half the volatility of the all share portfolio.

| 20 years | Average Return | Volatility | No of losing years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shares | 6.51% | 15.96% | 5 |

| Permanent Portfolio | 6.10% | 5.15% | 2 |

| 50:50 bonds & shares | 7.10% | 8.04% | 3 |

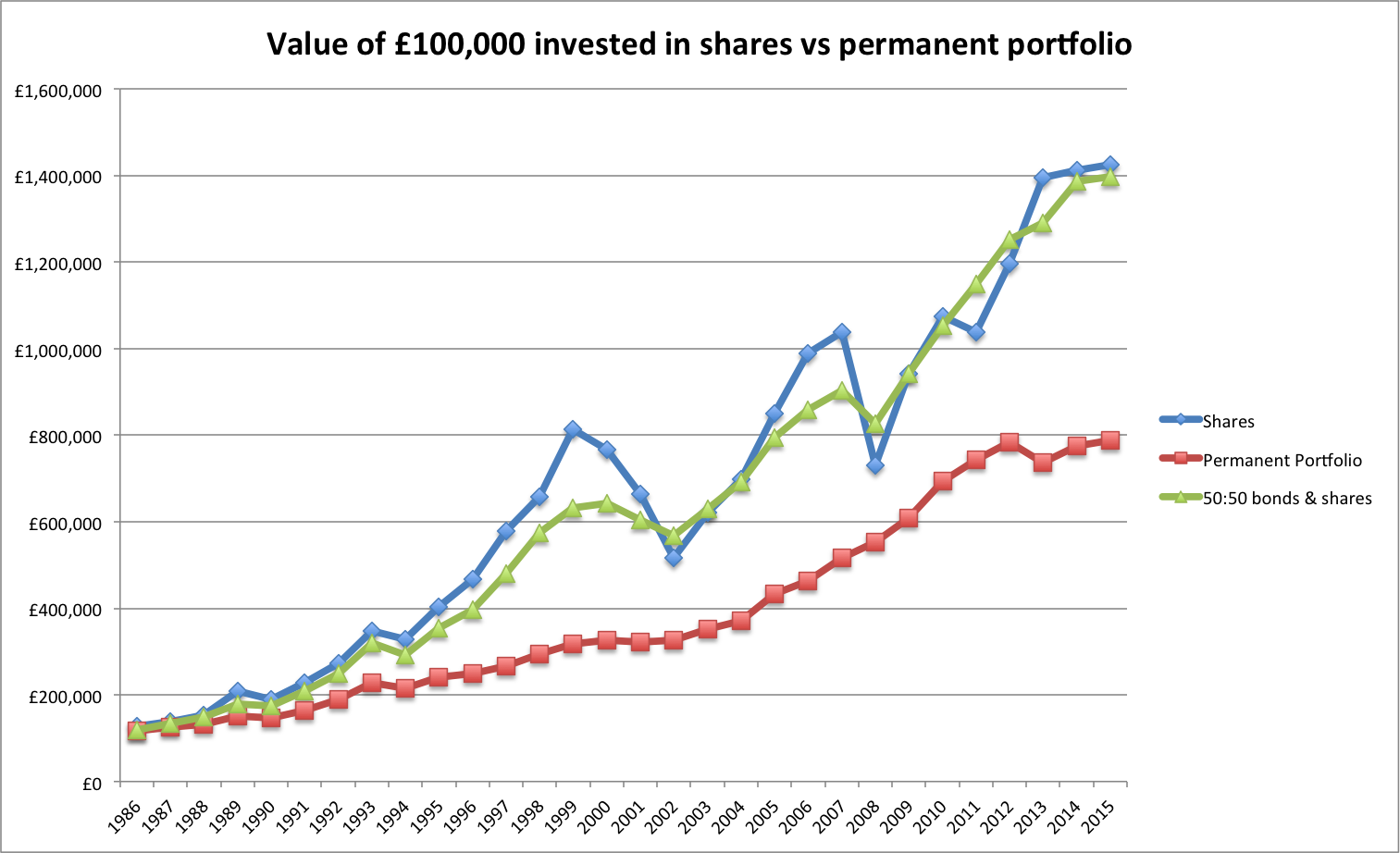

Over 30 years an all share portfolio has trounced the permanent portfolio (see chart below). Investors in shares have been rewarded handsomely for the extra volatility.

Again the value of the permanent portfolio has been a lot more stable and with fewer losing years. However, the difference in value over 30 years compared with an all share portfolio has been very big. The 50:50 portfolio was almost as good as the all share portfolio with much lower volatility but a higher volatility than the permanent portfolio.

| 30 years | Average Return | Volatility | No of losing years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shares | 9.26% | 15.77% | 7 |

| Permanent Portfolio | 7.12% | 6.47% | 4 |

| 50:50 bonds & shares | 9.19% | 9.62% | 5 |

Looking at these three charts above you can understand why so many financial advisors suggest investing a large proportion of a portfolio in shares if you don't need to access your money for a long time. In the past this advice would have been sound even though you could have achieved almost an equally good result with a 50:50 portfolio with a lot less volatility.

But what about the future?

Practical issues with asset allocation in today's markets

Spreading your money around can certainly reduce the swings in value that your portfolio might experience. However, having large chunks of money in cash and government bonds might make for a good night's sleep but could make it very difficult to build up a sizeable retirement pot.

With cash and government bonds paying next to no interest does it really make sense to have half your money invested in them as Harry Browne suggested? Having a quarter of your money invested in gold is also questionable. It pays no income and has been a more volatile asset than shares in the past without the rewards.

There's no doubt that investors today face a very hard time earning acceptable returns from their portfolio without taking lots of risk with their money. That said the growth in exchange traded fund (ETF) products have also given them lots of choice for investing in different assets and building their own low cost DIY asset allocation plan. You can research a vast range of ETFs and investment funds in SharePad.

For example, a cautious investor investing for at least ten years could consider the following strategy that could give them a reasonable chance of meeting their savings goal without staking everything on the fortunes of the stock market. It would give them exposure to a range of investments that should behave differently to each other in some way and reduce volatility.

- 50% invested in dividend-paying blue chip shares with a minimum yield of 3%. Remember to reinvest your dividends

- 10% invested in a corporate bond ETF

- 10% invested in a commercial property ETF. A fund that invests in real estate investment trusts or REITS

- 10% in a UK government bond ETF

- 10% in gold ETF

- 10% in cash

The portfolio should be rebalanced from time to time (not too often to keep the trading cost down) if the size of investments stray too far from their target allocations. So if your shares perform really well and become 60% of your portfolio you might sell to get back to 50% and reinvest the spare money back into the other assets you have chosen.

Here a keen private investor would still be able to enjoy managing their own share portfolio whilst spreading the risk around. As will all parts of DIY investing you are in charge and can decide where to invest your money in a way that suits you. You can make it as simple or as complicated as you wish to.

Further reading

If you want to explore asset allocation further there are some great books out there on the subject. They tend to be easy to read and are therefore very accessible to the layperson.

Two books that are worth reading are:

- The Intelligent Asset Allocator by William J. Bernstein

- All about Asset Allocation by Richard A. Ferri

Both these books push the investor towards investing in index funds. This might be useful for novice investors and for investors who want a simple way to gain exposure to alternative assets or certain foreign stock markets.

However, this approach might be a bit boring and not as rewarding for more sophisticated private investors. I believe that by cutting out the bad shares that make up a lot of the stock market - and index tracking funds - a private investor running a well researched portfolio of 10-15 shares can get a better result from their share portfolio.

To sum up

- Putting all your money in shares can be quite risky and is not suitable for all investors.

- There is a risk that shares might fall in value at the wrong time in your savings plan. You might not have enough time to make the money back.

- Volatility can make investors nervous and lead them to make mistakes.

- Spreading your money around in different assets can make the value of your portfolio more stable.

- Asset allocation is all about meeting your savings targets and controlling risk. You need to find the right mix of investments that can earn enough money without you worrying too much.

- You can take too little risk and fall short of your savings goal.

- ETFs have made it a lot easier to build a DIY asset allocation plan.

- A higher proportion invested in shares might work well for long-term savings plans as there is enough time for good years to offset bad years in the stock market.

If you have found this article of interest, please feel free to share it with your friends and colleagues:

We welcome suggestions for future articles - please email me at analysis@sharescope.co.uk. You can also follow me on Twitter @PhilJOakley. If you'd like to know when a new article or chapter for the Step-by-Step Guide is published, send us your email address using the form at the top of the page. You don't need to be a subscriber.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.