How to understand pension fund deficits

Many companies still have final salary pension fund schemes. Lots of them have significant funding shortfalls known as deficits. This means that the fund's assets are not big enough to pay all the future pensions it has promised to its past and current employees.

Pensions are a dry and complicated subject. Nevertheless they are very important issues for investors in company shares. You should always remember that a shareholder is only entitled to the profits and cash flows of a company after all expenses and liabilities have been paid. The more liabilities that are in front of you, the less money you are entitled to and the more risky your shares tend to be.

That's why I am going to use this article to shed some light on this important subject. At the end of it you will understand the big impact pension fund deficits can have on company profits and cash flows, the amount of dividends shareholders receive and the value of shares.

Phil Oakley's debut book - out now!

Phil shares his investment approach in his new book How to Pick Quality Shares. If you've enjoyed his weekly articles, newsletters and Step-by-Step Guide to Stock Analysis, this book is for you.

Share this article with your friends and colleagues:

Identifying big pension fund deficits

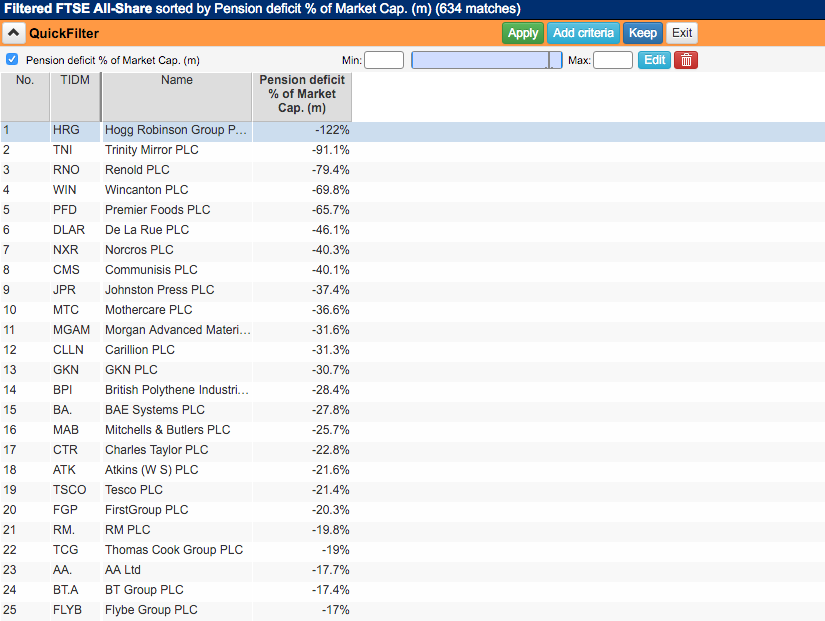

One of the ways to see if a company has a big - and potentially problematic - pension fund deficit is to compare it with the market value of its equity (market capitalisation). You can easily do this in SharePad using the Quick filter and Combine item functions.

As you can see, there are some companies with big pension fund black holes out there. You need to take great care in analysing these companies before buying their shares.

Defined contribution pension schemes

Many companies offer defined contribution pension schemes to their employees.

This is where the amount of money paid into the fund is known (it is defined). It is usually a percentage of the employee's salary. This is a known cash cost for the company every year. The amount paid reduces a company's profits and cash flow.

The amount of pension the employee will ultimately receive will depend on the amount that they and their employer contributes and the investment returns on the money invested. The company has no further obligations at all. Companies like this type of pension scheme because once they have paid a contribution they don't have anything else to worry about.

Defined benefit or final salary schemes

These pension funds are more problematic for companies. Here, the benefit - the employee's pension - is defined. It is usually based on a percentage of the employee's final salary.

The problem for the company is that they need to have enough money to pay the employee's pension for the rest of their life when they retire. This can end up being a very large sum of money and is not an easy number to work out. Companies employ actuaries to work it out for them.

These pension funds can become a big problem for companies when the amount of money they have set aside (pension fund assets) is less than the amount they will have to pay out in future pensions. Under these circumstances, the pension fund is said to have a deficit and the company has to find the money needed to make up the shortfall. When the deficit is a big number, a company may have to cut its dividend payments to shareholders. In extreme cases, the deficit may bankrupt the company.

This is the reason why most final salary schemes have been closed to new members and the benefits have been cut for existing ones. Companies have realised that the promises to pay large pensions for a long time is too expensive for many of them. BT's final salary scheme was closed to new members in 2001 but still remains a big problem for the company.

BT's final salary pension scheme

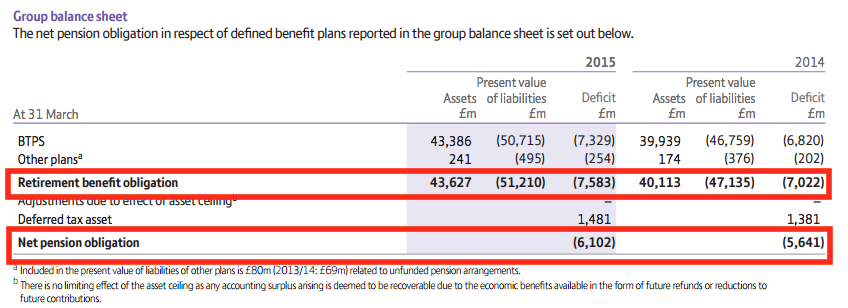

At the end of March 2015, BT's final salary pension fund had a deficit of £7.6bn as shown in the screenshot below. This was because the value of the fund was £43.6bn but the present value of its future pension promises was £51.2bn. The deficit is shown on the company's balance sheet as a liability and reduces the amount of shareholders' equity.

The net pension deficit or obligation was £6.1bn. The £7.6bn deficit had been reduced by a deferred tax asset of £1.5bn. This asset exists because if the company wanted to get rid of its deficit in full today it would have to make £7.6bn of payments into the fund and it would get tax relief of £1.5bn on those payments.

But how does a fund end up in deficit in the first place?

Let's take a look at how its assets and liabilities are made up. I'll use BT as an example to show you.

Pension Fund Assets

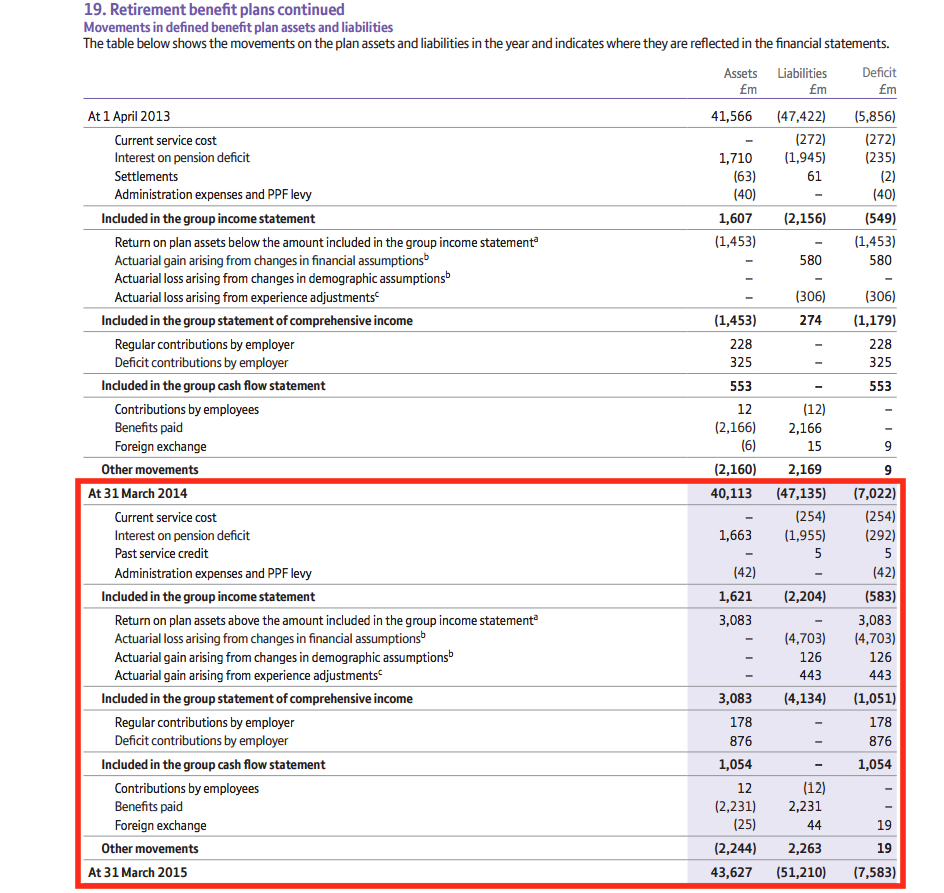

Above is a screenshot from BT's 2015 annual report. It shows how the assets and the liabilities of a final salary pension scheme are made up and how they change during a year. Let's start by looking at the assets first.

The assets of the pension fund are made up of the value of different investments such as shares, bonds, property and cash. The value of these investments have to be shown at their fair value. This is often the market value for investments such as shares and bonds. If there isn't a market valuation available, the actuary will estimate a value. At the end of March 2014, the value of the fund's assets was £40.1bn.

The actuary will then estimate the annual investment return on those assets - price changes plus any income received such as dividends. Rather obscurely this is called interest on pension deficit in BT's accounts above. The annual investment return was assumed to be £1663m for the year to March 2015. £1663m divided by the starting asset value of £40113 tells us that the estimated return was 4.14% - a similar assumption to 2014 of 4.11%. This return is added to the fund's asset value and is also treated as interest income in BT's income statement (more on this later).

An administrative expense of £42m was paid which reduces the asset value.

We then have an addition of £3083m. This represents the extra amount of money earned from investment returns above the amount assumed by the actuary (£1663m). What this is telling us is that the fund produced total investment returns of £4746m (£3083m + £1663m) during the year.

Then we have the amount of £1054 that BT paid into the fund. This is made up of regular contributions of £178m and top up payments of £876m to reduce the deficit. This is a cash outflow and a large one at that. This is a key number for investors to pay attention to as it has the biggest impact on how big their dividends might be.

Next comes the contribution of £12m paid by employees which adds to assets.

The biggest reduction in assets comes from the amount of money actually used to pay pensions - £2244m. After this has been paid, the fund ends the year with assets of £43.6bn or £2.5bn more than it started with.

This is encouraging but is only half the story. You have to take into account what has happened to the liabilities as well.

Pension Fund Liabilities

These are the present value of all the future payments that have to be made to current and future pensioners. How this number is arrived at involves some very complicated calculations which are worked out by the actuaries. At the end of 2014 the value of these liabilities was £47.1bn.

In order to work out the value of the liability the actuary uses the following variables:

- The rate of increases in workers' salaries between now and their retirement date.

- When the workers will retire.

- What proportion of their final salary they will be paid.

- How long they will live after they retire. In other words how long the company will have to pay the pension for.

- The rate of inflation in the future as pension payments are often linked to inflation.

A liability will be worked out for each worker and then all the liabilities will be added together. The value of this liability then has to be discounted to a value today or at the balance sheet date. The discount rate is based on the yield of good quality bonds (which is open to interpretation). The lower the yield on those bonds the higher the present value of the liability. Many pension fund liabilities have been rising in recent years due to lower interest rates on bonds and the assumption that pensioners are living longer.

Starting with a value of £47.1bn, a current service cost of £254m is added to the liability. This is the amount of future pension benefit that current employees have earned during the year.

Then an interest expense is added to the liability. This interest charge is also treated as an expense in the income statement. The £1955m of interest expense is effectively the unwinding of part of the total present value of liabilities. It occurs because part of the liability has become closer to being paid.

We then see a big addition to the liability of £4.1bn due to changes in assumptions versus those assumed by the actuary. BT explains the reasons for this change in a footnote.

Then the other big number is the £2231m paid out to pensioners. This reduces the liability because it has been paid and doesn't need to be paid again.

However, the value of liabilities ended the year more than £4bn higher than when it started and led to the overall value of the deficit increasing.

Final Salary pension schemes and profits

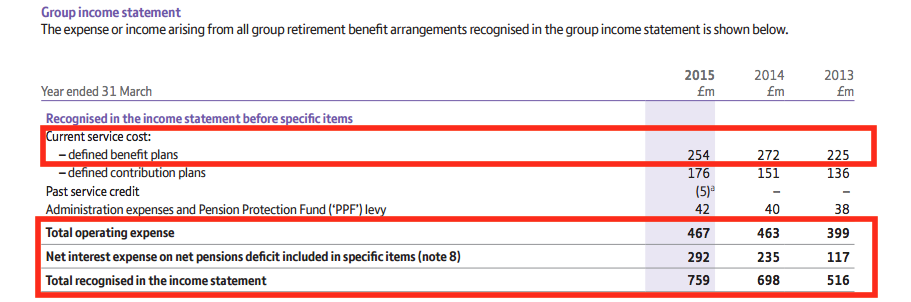

The pension fund surplus or deficit is shown on a company's balance sheet. The costs associated with final salary pension schemes are treated as expenses in a company's income statement.

BT has charged £254m of current service cost and £292m of interest (£1663m of assumed investment returns less £1955 on interest on pension fund liabilities) as an expense in its income statement. The interest part of it has been included in exceptional (one-off) items and not used to calculate the company's underlying profits. Not all companies follow this approach and it could be seen to be slightly aggressive accounting by BT.

On the other hand, you could argue that these amounts of interest income and expense are not real cash flows and it is quite right to exclude them.

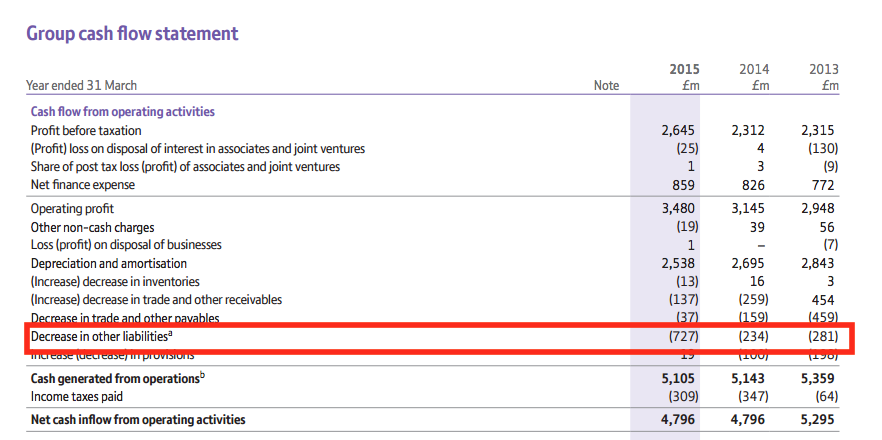

Impact on cash flows

What the company actually pays into the final salary is much more important. This is what affects the company's annual free cash flows and its ability to pay dividends to shareholders.

BT paid over £1bn into its final salary pension fund last year. £168m was an ordinary contribution which was less than its current service charge (the amount of future pension benefit earned by employees during the year of £254m) and £875m was a top-up payment with the aim of reducing the deficit.

In the company's operating cash flow, the excess cash paid over the current service charge expensed in the income statement will be shown as a cash outflow. With £1083m of cash paid against the £254m of current service charge expensed the cash outflow would be £789m and would reduce BT's operating cash flow. This is shown in the £727m decrease in other liabilities below.

As you can see in the note above, BT made another top up payment of £625m in April 2015 with another £250m to be made before March 2016. These top-up payments have been agreed with the pension fund trustees and will total £8.7bn between 2015 and 2030, That is £8.7bn that cannot be paid as dividends to shareholders.

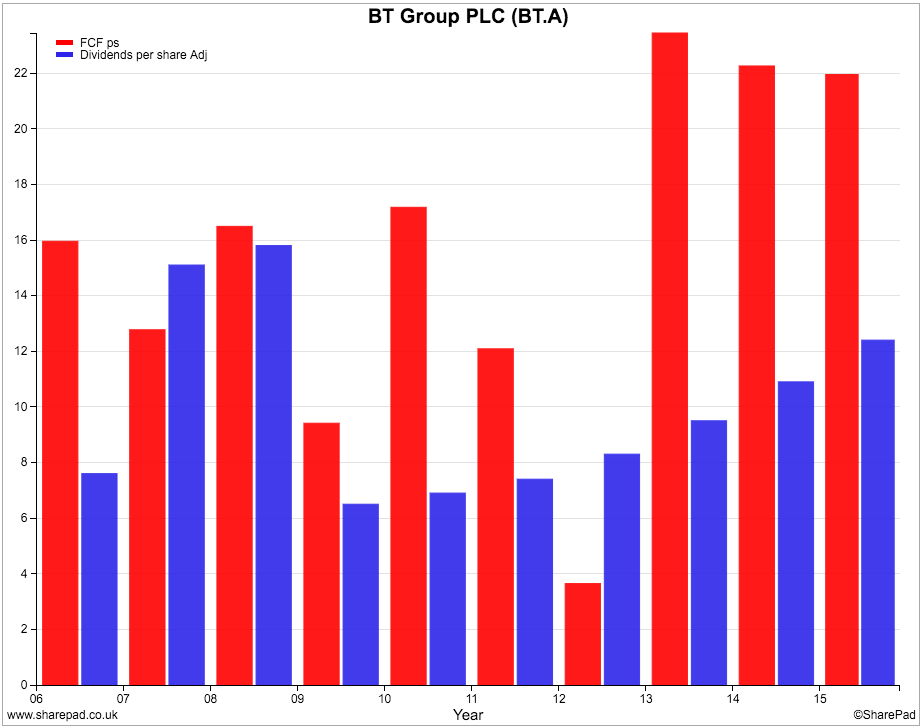

Implications for dividend payments

Despite the large pension deficit payments that are being paid, BT has still been producing enough free cash flow to comfortably cover its dividend payments as shown in the chart above. This is not always the case with other companies with pension fund deficits

Valuation Issues

Just like borrowed money, pension fund deficits are real liabilities that require cash payments to meet them. These cash flow requirements reduce the amount of money left over for shareholders and therefore reduce the equity value of a company. In short, pension fund deficits are a big deal for shareholders.

This is why you need to take into account the value of pension fund deficits when you are valuing a company using enterprise value (EV). EV is a market value for a company's total assets.

The accounting value of a company's assets is the same as the value of its total liabilities plus equity:

Total Assets = Total Liabilities + Equity

So a proper estimate of enterprise value should include the value of any pension fund deficit because it is a significant long-term liability.

EV = Market value of Equity (Market Cap) + Total Borrowings

+ Pension Fund Deficit + Minority Interests

Many takeovers of companies have failed due to the size of the pension fund deficit. The trustees of the fund will often insist that the deficit is eliminated if the company is taken over. The buyer will have to factor this into the purchase price. The flotation of Royal Mail on the stock exchange was only able to happen when the pension fund deficit was transferred to the government.

So if you are using multiples of enterprise value such as:

- EV/Sales

- EV/EBITDA

- EV/EBIT

- EBIT/EV

The EV is more prudent if it contains the value of the pension fund deficit. A company might look cheap when it is ignored but quite expensive if there is a big deficit. In SharePad, all enterprise values and EV multiples are adjusted for pension fund deficits.

To sum up:

- Final salary or defined benefit pension funds can be hard to understand.

- Deficits reduce the equity value of a company and the value per share.

- Deficits have to be cleared which reduces the cash flows available to pay dividends

- In extreme circumstances, a big pension fund deficit can bankrupt a company.

- Pension fund assets and liabilities are based on lots of assumptions and move around a lot from year to year.

- The cash paid into a pension scheme can be materially different from the expense in the income statement. Big deficits can lead to free cash flows being considerably less than reported profits.

- Comparing the size of the pension fund deficit with a company's market capitalisation is a useful way of spotting problem companies.

- Prudent valuations of companies need to include the value of any pension fund deficit.

If you have found this article of interest, please feel free to share it with your friends and colleagues:

We welcome suggestions for future articles - please email me at analysis@sharescope.co.uk. You can also follow me on Twitter @PhilJOakley. If you'd like to know when a new article or chapter for the Step-by-Step Guide is published, send us your email address using the form at the top of the page. You don't need to be a subscriber.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.