Stock Watch: B&M European Value Retail

Should you buy the shares of a company in an IPO (initial public offering)? Usually, my answer to this question would be a resounding "no", unless it is the government that is selling the shares (the UK government has a track record of selling off companies cheaply).

IPOs occur when a company lists its shares on the stock exchange for the first time. Stockbrokers love them because they can pocket a handsome fee from selling the shares to investors. The amounts of money they can earn from them dwarfs the amount of money they usually make from the day-to-day business of trading shares for their customers.

Investors seem to like them too. They are often attracted by the thought of owning something new and the possibility of getting in early to make a killing on the shares.

Sadly, buying shares in an IPO can often lead to disappointment. That's because IPOs are often used to maximise value for the selling shareholders with little thought of leaving something on the table for the new buyers. This means that the shares in IPOs are often sold at very rich prices. After the excitement of the IPO has gone away, the share price often settles at a much lower level and the buyers are left nursing their losses.

However, not all IPOs follow this path - at least initially. There are a few happier stories out there. B&M European Value Retail (B&M) floated on the stock exchange in June 2014 at 270p per share, and despite a bumpy first six months, those that have hung on to their shares are currently in the money.

Will the good times continue? It's time to open up ShareScope and SharePad to try and find out.

Phil Oakley's debut book - out now!

Phil shares his investment approach in his new book How to Pick Quality Shares. If you've enjoyed his weekly articles, newsletters and Step-by-Step Guide to Stock Analysis, this book is for you.

Share this article with your friends and colleagues:

Background

B&M is best described as a discount retailer. Its aim is to sell products such as branded consumer goods and non-grocery products (think homewares, toys, DIY and seasonal products) at very cheap prices - often much cheaper than they can be bought from supermarkets and specialist retailers.

The company began life in 1976 with a single store in Blackpool. Since 2004 it has grown rapidly under the ownership of the Arora family who expanded the business from just 22 stores to 450 in March 2015. B&M has also bought a discount retailing business in Germany.

The company has been extremely successful at tapping into the growing power and influence of discount retailers. This has seen increasing numbers of people flock to shops such as Aldi, Lidl, Poundland and Home Bargains, either through necessity of for the excitement of snapping up some bargains.

Let's take a look at its recent financial history. ShareScope and SharePad have financial data going back to 2012. This is similar to the information you will find in the IPO prospectus.

Prospectuses are great sources of information about a company from which you can learn a great deal about how it makes money and the markets it operates in. I'd go as far to say that they are probably the most valuable source of public information that a private investor can get their hands on when it comes to researching a company. (You can access B&M's prospectus here).)

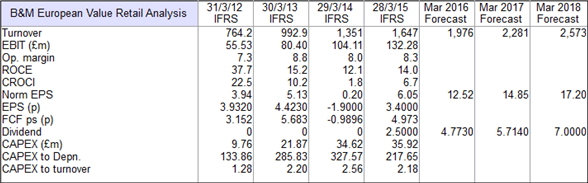

B&M's financial history is shown in the ShareScope result table above. It shows a company that has been doing very well. The business has seen rapid growth. Turnover and profits have more than doubled during the last three years and profit margins have been going up.

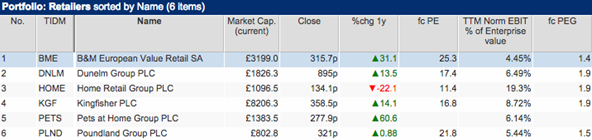

An operating margin of 8.3% in the year to March 2015 looks very impressive compared with the margins currently being earned by UK supermarkets. But what about other similar retailers?

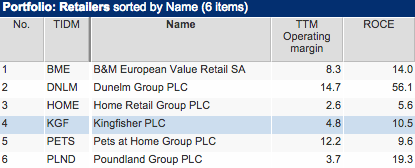

A great feature of ShareScope and SharePad is the ability to compare similar companies on a huge range of financial measures - by using a sector filter or by putting them into a portfolio. I've compared B&M with some of its peers on the basis of operating margins and return on capital employed (ROCE) below.

Here you can see that B&M doesn't currently match the profit margins of Dunelm Group (a seller of homewares) or Pets at Home. However, it looks significantly more profitable than its much bigger peers such as Kingfisher and Home Retail Group.

One measure that needs watching with B&M is the decline in its ROCE which has fallen sharply since 2012. A fall can probably be explained by the company's rapid expansion in recent years and the fact that new stores take some time to mature and reach their expected levels of profits and ROCE.

ROCE is usually a very good measure of company performance but needs to treated with caution with retailers because many of them tend to rent rather than own their stores. This distorts the ratio by understating the assets and capital employed used in a business. I'll explain why.

Companies can be locked into long-term agreements to rent stores which are difficult and expensive to get out of. Many people argue that these commitments are liabilities and are a form of hidden debt and that the value of them should be shown on a company's balance sheet. By my reckoning, B&M's future rent commitments amount to over £600m of hidden, off balance sheet debt. If this figure was added to capital employed, ROCE would fall from 14% in 2015 to 10.8%. (I've written a separate article on how this is calculated here.)

Based on the financial information available, B&M looks like it is good at turning its profits into free cash flow. However, this can also be explained by the company renting rather than buying or building its stores. The cash outlay of paying a rent on a new store is a small fraction of the cost of actually buying or building one. If B&M was buying or building its own stores then, given the rate of recent expansion, huge amounts of cash would have been flowing out of the business and free cash flow would have been significantly negative.

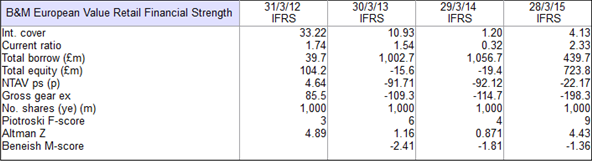

On the face of things, looking at the company's financial strength it seems that there is little to worry about. Interest cover of 4 times is quite low but doesn't signal that the company is in any imminent danger of not paying the interest on its borrowings, especially given the strong growth in profits.

B&M has a maximum Piotroski F-score of 9 which indicates a strong improvement in financial performance whilst an Altman Z-score of 4.43 suggests that it is not likely to have financial difficulties soon.

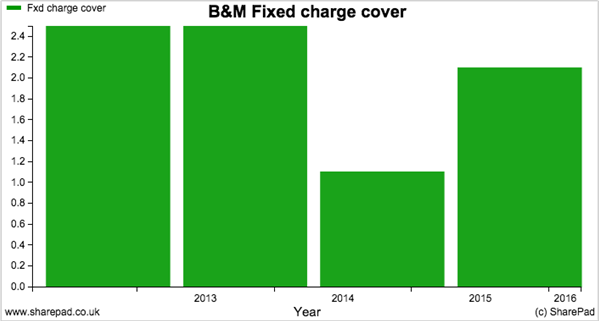

Given the large amounts of rents paid on its stores, a key ratio to look at with B&M is its fixed charge cover. This looks at how many times a company's profits can cover its rent and interest charges.

To calculate this ratio, you take a company's EBIT and add the rental expenses to it. You do this because EBIT is stated after rental expenses have been already deducted. You want to know the money available to pay rents and interest so you need a profit number before rents have been taken away from it. Once you have this number, you divide it by the rental and interest expenses.

For the year to March 2015, B&M had normalised EBIT of £157.6m, rental expenses of £74.4m and normalised net interest expenses of £38.1m. Its fixed charge cover was therefore:

(157.6 + 74.4)/(74.4 + 38.1) = 2.1 times

This is quite a low figure but not uncommon amongst retailers who rent their stores. Anything below 1.25 times would be a worry. Fixed charge cover has been a great way to spot retailers in trouble in the past such as HMV, Game Group and Woolworths. These companies did not have huge amounts of debts on their balance sheets but the rental commitments crippled them when profits started falling. B&M's fixed charge cover shouldn't give investors any real cause for concern at the moment.

SharePad calculates fixed charge cover for you. As with all ratios the trend is as important as the absolute number.

B&M's fixed charge cover has been falling slightly due to the rapid growth in new stores. As the profitability of new stores increases, the fixed charge cover should improve. However, as B&M has big expansion plans for lots of new stores this might not happen for some time yet.

Can B&M keep on growing its profits?

For a retailer such as B&M to be a profitable long-term investment it needs to be able to keep on growing. This can be easier said than done. For years Tesco kept on growing and seemed unstoppable only to eventually come unstuck and see its share price collapse. Can B&M avoid the same fate?

To try and find out I am going focus on some key areas of B&M's business. In particular I am looking for the answer to two important questions:

- Whether or not it has a competitive edge over its peers?

- Can it open a lot more stores and keep growing profits from its existing ones at the same time?

I am going to focus just on the UK business as this is likely to be the main driver of B&M's profits and ultimately the value of its shares.

B&M's competitive edge

To be a successful business you have to be able to do something that your competitors cannot. Usually this means you have a specific product or service that is better and can't be copied. Or you can offer the same products or services for a lower price because you have lower costs.

B&M's proposition to customers is that they can buy selected branded goods and a range of non-grocery products a lot cheaper than they can from the big supermarkets and specialist retailers. If you walk around one of its stores then you'll find out this is definitely the case. However, if you are thinking of investing in the company you need to understand why it is able to do this.

When you first start thinking about this, it is really difficult to believe how a retailer which is tiny in comparison to some of its giant competitors can offer the same or similar goods at cheaper prices.

Here's how B&M does it:

First and foremost, B&M is a very focused retailer. By that I mean that it concentrates on selling a limited stock of goods. So for example, it might sell only two brands of washing tablets rather than ten. This is repeated across its whole range of goods so that it is only really selling around 5500 different products whereas some of its competitors might sell up to 30,000.

The company never gets bloated with too much stock as it operates on a one good in, one good out policy and rarely holds more than three months of potential sales of a product in stock. Holding too much stock eats up cash flow and B&M's policy will minimise this risk.

B&M's strategy allows it to concentrate its buying power behind particular brands so that it can buy them at a cheaper price and pass the savings on to customers. By selling lots of a particular product it can then go back to the supplier and negotiate a better deal. The supplier is usually happy to do this as B&M is helping its business to grow as well.

Secondly, the company has a stake in a Far-East buying and importing company which allows it to import goods from places such as China at very good prices. It has built up very good long-standing relationships with a network of over three hundred suppliers by treating them well and paying them quickly. In return B&M has been able to stock its stores with a wide range of non-grocery goods such as toys and homewares that sell for very compelling prices which the competition finds hard to match.

Thirdly, B&M adopts a flexible approach to trading in its stores. It does this by stocking seasonal goods at the relevant times of year to entice more customers into its stores.

The potential for future growth

City analysts expect B&M to keep on growing its sales and profits at a rapid rate. The company has an ambition to grow its store numbers from 450 at the end of March 2015 to ultimately 850 over the next few years.

On the face of things this seems very plausible. Consumers are flocking to discount retailers in droves and it seems that there will be plenty of stores to buy from struggling retailers who are looking to downsize. If B&M can get to 850 stores then there is a possibility that its profits could be a lot higher in a few years' time than they are today. However, given the high valuation attached to its shares (more on this shortly) it seems that this might be being taken for granted already.

To be able to grow profitably, B&M will have to overcome three big risks.

Saturation, maturation and cannibalisation

You only have to look at the fate of Britain's supermarkets to see what happens when they open up too many stores. At the moment, one of the many problems they are facing is that there are too many supermarkets chasing too little custom and profits have fallen as a result. Could the same thing happen to B&M and the other discount retailers?

Quite possibly.

Aldi, Lidl, Poundland and Home Bargains all have ambitious plans to grow their businesses. Home Bargains in particular has a similar strategy to B&M. It wants to eventually have around 800 stores and branch out from its north of England roots into the south. This could push up competition for sites and make it harder for B&M and others to make decent money from them.

There's also the risk that the discount retail market will become oversupplied with all these new stores from different retailers just as has happened with the supermarkets. Another thing to ponder is the response of the supermarkets themselves to the threat of the discounters. Could they adopt a similar concentrated buying strategy and make their prices much more competitive?

Then there's the performance of B&M's stores itself.

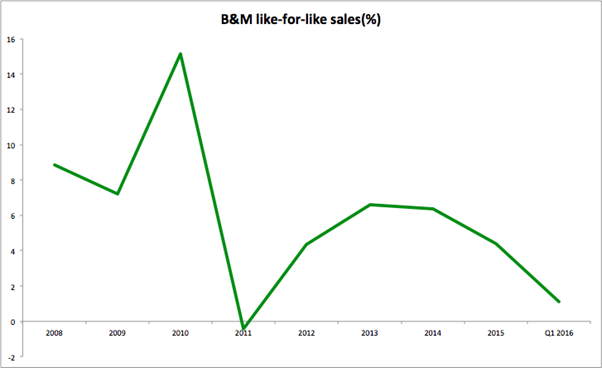

A key measure of a retailer's performance is known as like-for-like-sales (LFL) - the change in sales from stores that have been open at least one year. I got this data from the annual report and flotation prospectus.

Apart from a blip in 2011, B&M has been very impressive on this measure as customers keep coming back to its stores to buy more goods and new ones start visiting.

However, LFL sales need to be interpreted with caution. The reason for this is that new stores take time to mature - to get up to their potential levels of sales and profits - and this can take longer than a year to achieve.

What this means is that when you have been opening lots of new stores as B&M has, there can be a large number of the total store portfolio that are just over a year old where sales are still building up. The sales from these stores are included in the calculation of LFL sales and can give the impression that underlying sales are strong when actually it is the effect of stores maturing. As the store portfolio gets bigger, these maturing newer stores have less of an impact on overall LFL sales which can cause them to grow at a slower rate or even start falling.

As you can see from the chart above B&M's LFL sales have slowed significantly recently. This could be a blip or the start of a worrying trend. This needs to be watched closely.

The other thing to keep an eye on is something known as cannibalisation of sales. This is when a new store opens close to an existing store and starts taking customers and sales away from it which stunts the growth of the business as a whole. This is a major risk for an expanding business like B&M. So far, it seems that this has not been a problem as the company is opening stores in areas like the south of England where it does not have a lot of existing stores.

Given the apparent strength of B&M's business model, if it can overcome these risks then it is entirely possible that it can grow its profits significantly in the years ahead.

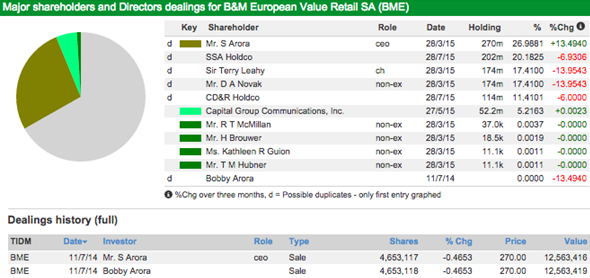

Insider ownership

Buying the shares of a company where management owns a large chunk of shares is usually seen as a good thing. Most of the time it means that their interests are aligned with the other shareholders and so they are motivated to do the right thing by them.

There is nothing to suggest that this isn't the case at B&M. The Arora family still own around one third of B&M's shares having sold a large chunk in the IPO and shortly after. However, such a big shareholding can make some investors nervous that a large chunk of shares could come on to the market in the future and depress the share price. This is possible and investors should be mindful of this risk. However, if the business continues to be successful, there may be plenty of new investors who might be happy to buy the shares. It would also have the effect of increasing the liquidity of the shares and make them easier to buy and sell on the stock exchange.

A value retailer at a premium price

If past performance is anything to go by, it seems that there's a lot to like about B&M as a business. The stock market seems to think so and has put a very punchy price tag on its shares.

On just about every valuation measure, B&M looks richly valued. It has a high forecast PE ratio of over 25 times and a low EBIT yield of 4.45% at the current share price of around 316p. Its shares are also more expensive than its peer group. There's no doubt that anyone buying the shares today is being asked to pay up front for a lot of the potential profits growth and this is undoubtedly a major risk. If the expected profits don't come through then you could lose a lot of money.

One of the most valuable things you can do as an investor is never forget how you are rewarded for owning a share of a company. The returns you ultimately receive a determined by just three things:

- Company profits

- The valuation the stock market places on those profits such as a PE ratio

- Dividends received

So your total return is the change in share price (reasons 1 and 2) plus any dividends received. When I am looking at a share, I try and work out what my potential returns might be looking at different scenarios for profits, valuations and dividends. The number of scenarios are endless but I'll show you a couple of examples below.

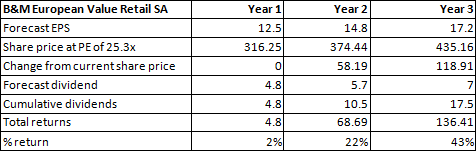

First of all, I take the forecast earnings per share and dividends per share from ShareScope or SharePad and see what kind of money I could make if those forecasts turn out to be correct and the stock market continues to value the shares at its current PE multiple.

As you can see, in three years the change in share price and dividends received could give you a nice return of 43% on a buying price of 316p which would be more than satisfactory.

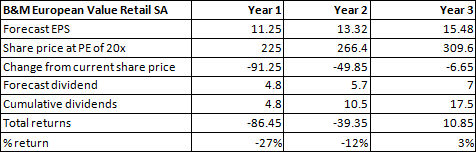

However, good investors focus just as much of their time working out their risks - how much money they could lose - rather than taking gains for granted. Let's see what might happen if EPS comes in 10% less than expected (multiply the forecast EPS by 0.9 to get this number) and the PE ratio drops to 20 which is still a high valuation. I'll assume that expected dividends stay the same to keeps things simple.

After three years, you would just about break even. This clearly shows the risks involved when buying shares that are already highly priced. Just as a higher valuation (such as a higher PE ratio) can make you richer, the process can work in reverse as well.

The question is: are you more convinced by the growth story than the saturation, maturation and cannibalisation risks?

If you have found this article of interest, please feel free to share it with your friends and colleagues:

We welcome suggestions for future articles - please email me at analysis@sharescope.co.uk. You can also follow me on Twitter @PhilJOakley. If you'd like to know when a new article or chapter for the Step-by-Step Guide is published, send us your email address using the form at the top of the page. You don't need to be a subscriber.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.