What the fallout from the EU referendum means for stock market investors

I have to admit to being quite surprised how the stock market - and some shares in particular - have performed since the UK's decision to leave the EU on 23rd June. Predicting the future is an impossible task but the moves we have seen in some of the financial markets over the last week or so have been significant and do have implications for anyone managing their own money.

Let's have a look at what's been going on and consider some of the questions that investors should now be pondering?

Phil Oakley's debut book - out now!

Phil shares his investment approach in his new book How to Pick Quality Shares. If you've enjoyed his weekly articles, newsletters and Step-by-Step Guide to Stock Analysis, this book is for you.

Share this article with your friends and colleagues:

The fall in the value of the pound

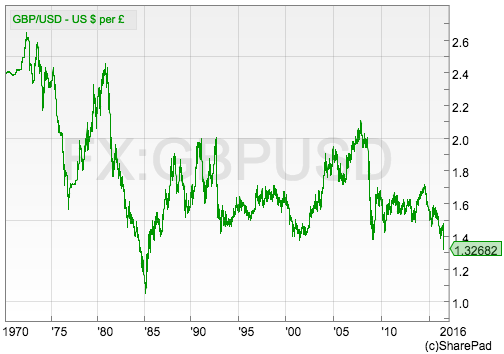

We have seen a sharp fall in the value of the pound. It will buy less in foreign currencies today than it would have done just over a week ago. At midnight on 23rd June, £1 bought around $1.50. It now buys less than $1.33 - the fewest number of US dollars since 1985.

There has also been a big fall in the value of the pound against the euro. A pound now buys less than €1.20. A year ago it bought over €1.40.

What does this mean for stock market investors?

Well let's start with the bad news first. Companies importing goods and raw materials from abroad are going to see their costs go up; they are going to need to spend more pounds to buy the products and materials they import. If they can't pass these higher costs onto their customers then their profits might not grow as fast as they previously thought or might actually fall instead.

The price of food, fuel and overseas travel for UK residents will go up as well. This means that they will have less money in their pockets to spend on other things. This is the reason why some economic experts have suggested that the UK economy might fall into a recession.

This would be bad for the profits of companies which are heavily exposed to the fortunes of the UK economy. As you can see in the table below, property and banking shares have been hammered.

But it's not all bad news.

Companies which earn a large chunk of money overseas are probably going to see their profits go up. For example, a company with operations in the US had to earn $1.50 in order to make £1 of profit just over a week ago. It will only have to earn around $1.33 now. The goods and services of UK exporters will also be cheap as foreign buyers will need less money to buy sterling.

It is important to bear in mind that annual profits and cash flows earned overseas are translated back into pounds at the average exchange rate for the year not the current or spot rate. In 2015, the pound averaged $1.528. So far in 2016 it has averaged $1.432.

If it stays around $1.33 for the rest of 2016 then the average rate for the year will be $1.38 - a 10% devaluation and a nice boost to overseas profits priced in pounds. So it is no surprise to see that the share prices of companies with large overseas earnings have gone up a lot.

However, the effect in 2017 will not be as big unless the pound falls further in value. Does this mean that people have got a bit carried away as the boost to profits might be a one-off?

Have the share prices of overseas earners gone up too much?

Are some of the shares that have benefited from this change in sentiment now overvalued?

Consumer brands companies such as Diageo, Reckitt Benckiser and Unilever trade on forecast price to earnings ratios (PEs) of around 25 times or slightly more. Very few people would argue that these represent attractive valuations. They look even more expensive when you compare their share prices with their last reported free cash flow per share.

If you look at the earnings power value (EPV) of these companies, you can see that some of them look quite expensive based on their current trading profits continuing forever. For example, Diageo's current profits only explain just under half of its enterprise value (EV) assuming investors require a return of 8%. More than half of its EV is dependent on future profit growth. (For more on EPV, click here.)

So profits are going to have to grow or investors are going to have to demand a lower interest rate (return) in order to justify the current share price - which may or may not be possible.

Before the fall in the pound's value, expectations for profits growth for many of the companies listed above was quite modest. Yet their shares have commanded high valuations for some time now as they are seen as dependable earners in most economic climates, with businesses that have strong competitive advantages or economic moats.

In some instances, investors have been viewing the companies as being almost bond-like. They think that their profits, cash flows and dividends are so dependable that the shares can justify having very high valuations - or low interest rates - attached to them.

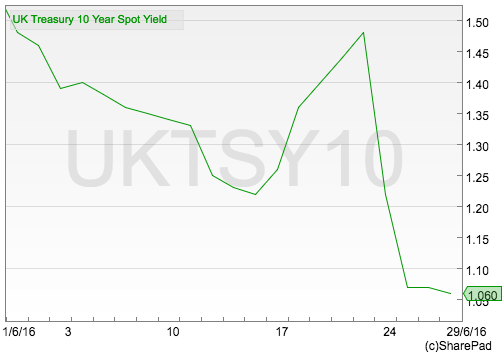

This theme may have been strengthened during the last week as mutterings from the Bank of England about cuts in interest rates and more monetary stimulus have pushed government bond yields to record low levels.

Do low bond yields justify higher share valuations?

Gilt yields - the interest rate the UK government has to pay to borrow money - have collapsed. The UK government can now borrow money for ten years at a rate of just over 1%.

Gilts are seen as very safe investments. As the UK can print its own money it is very unlikely that an investor will not get their money back at the end of ten years. What that money will buy then is another matter.

Government bond yields elsewhere across the world have gone to 0% and in some cases are even negative. Why on earth would you want to invest in them? You might as well put your money under a mattress. I guess nervous investors just want to hang on to the money they have got and sleep well at night.

For others looking for a source of income to live on or who have liabilities to meet in the future (such as pension funds) then the stock market might be the only place they can invest their money.

It is this view that there are few alternative sources of income that may continue to prop up the stock market and even push it higher. It is the reason why high quality companies with strong brands, dependable cash flows and high returns on investment can command higher stock market valuations. On the other hand, it could also be a big warning sign that shares have become too expensive and too risky.

To understand this, consider some reasonably straightforward stock market maths.

To me, investing is all about interest rates. I like to buy the shares of companies that earn a high rate of interest on the money they invest - a high return on capital employed (ROCE) or free cash flow return on investment (CROCI). The key to making money from these shares is not paying too much money for them. In other words I need to buy at a share price which gives me a reasonable rate of interest for starters. This can be measured by a share's earnings yield (EPS/Price) or free cash flow yield (FCFps/Price).

So how do you go about working out how much you should pay for a share?

The first thing you should do is work out what a company's cash profits are.

Basically, you take post-tax profit add depreciation & amortisation back on and then subtract stay-in-business capex (click here to read more about this).

Then you can work out the maximum share price you should pay for those cash profits. This is how people like Warren Buffett and Terry Smith go about valuing shares.

Here's my take on this approach below.

The straightforward approach is to divide your estimate of cash profits per share by the yield on government bonds. So profits of 10p per share would give a valuation of 1000p or £10 (10p/1%).

Hold on a minute. This would mean the shares would have a profit multiple of 100 times (1000/10). Surely that's ridiculous?

It is.

There is a good case for arguing that bond yields are being kept artificially low in order to stimulate the economy. In other words, bonds are overvalued. So using overvalued bond yields is going to give you overvalued share yields or profit multiples. (I've written more on this subject in this article).

To get around this problem you need to adjust the bond yield. Over the last thirty years, UK 10 year government bond yields have been around 3% higher than inflation. With current RPI inflation (May 2016) of 1.4% this would imply a minimum interest rate of 4.4%. If bond yields were 5% then no adjustment would be needed as they would be 3% more than inflation and would be more sensibly valued.

| 10 year gilt yield or Inflation rate (A) | 1.40% | 5% |

| Add on: Inflation buffer (B) | 3% | 0% |

| Minimum interest rate needed C = A+B | 4.40% | 5% |

|---|---|---|

| Implied maximum profit/cash flow multiple D = 1/C | 22.7 | 20 |

Low bond yields are often seen as a sign of low inflation ahead. But the point is this: if ten year bonds only offer a return of 1%, high quality shares offering a yield of 4.4% or a price multiple of 22.7 might be reasonable investments if profits can keep growing. In other words, low bond yields can justify high share prices.

The key issue here is growth. If profit growth stalls or even falls then paying these kinds of profit multiples is not going to make you much richer. Instead you are likely to lose a lot of money.

The other thing you might want to bear in mind is what the devaluation of the pound will do to inflation. If inflation goes up because of higher prices of imported goods then the minimum interest rate will rise and the maximum price multiple will fall. This would not be good news for share prices in general.

Pension fund deficits to rear their ugly heads again

Whilst stock market bulls might be getting excited by the effect the fall in the value of the pound and low interest rates might have on the value of their share portfolios, there is a nasty side effect for some companies.

Low interest rates are bad news for companies with final salary pension funds. These promises to pay pensions to employees cost more as interest rates fall. In financial jargon, the liability goes up.

If the value of the pension fund's assets (investment in shares, bonds, property etc.) does not go up as well then there is a chance that the company's pension fund will be less than the value of its liabilities and it will be in deficit. Or an existing deficit will get bigger.

Working out pension fund liabilities is a complicated task. However, a very simple - oversimplified - way of understanding the impact on interest rates on them is to consider the following example. It's not how liabilities are worked out in practice but it will help you understand them.

Say an employee's pension based on their final salary is £10,000 per year. If interest rates on government bonds are 10%, the employer needs £100,000 of bonds to produce that income (£100,000 x 10%). If interest rates fall to 5%, the employer would need £200,000 to produce £10,000 per year (£20,000 x 5%). So, falling interest rates are bad news for companies with final salary pension schemes.

If interest rates on bonds are going lower then some companies could have to put more cash into their pension funds. This could mean that there is less cash spare to pay dividends to shareholders.

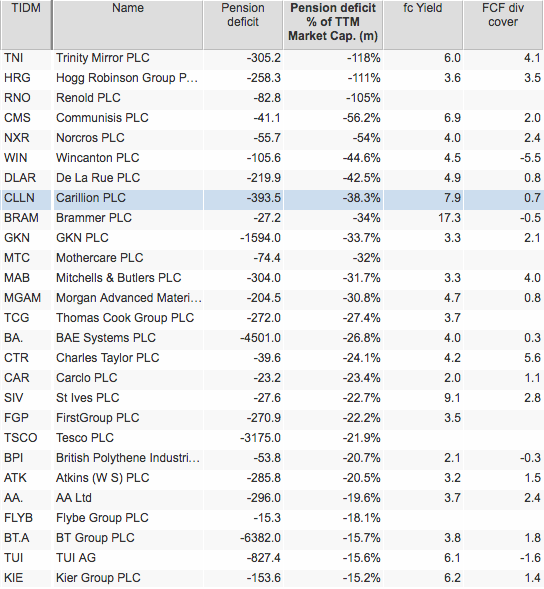

The table below shows a SharePad filter looking for companies where the pension fund deficit is a significant part of their market capitalisation. The higher the percentage, the bigger the potential headache the pension fund could be for shareholders.

For example, companies such as Carillion have a big pension fund deficit and a dividend which is not covered by free cash flow. This dividend could be at risk and this is evidenced by the high dividend yield attached to its shares.

For companies such as this you need to study their pension fund positions very closely (click here to read more about this). Pay particular attention to the size of the liability and not just the deficit.

Where's the cheap stuff?

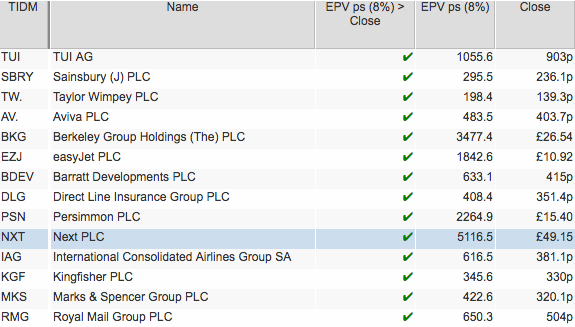

As I mentioned in my article last week (Sifting for bargains amid the stock market carnage) the market volatility has thrown up some interesting UK shares with low valuations. Below is a list of shares in the FTSE 100 where the current valuation is implying no profits growth again from current levels - i.e. they are trading below their current EPV.

You'll need to convince yourself that the stock market is wrong about these companies and that their profits will grow again.

If you have found this article of interest, please feel free to share it with your friends and colleagues:

We welcome suggestions for future articles - please email me at analysis@sharescope.co.uk. You can also follow me on Twitter @PhilJOakley. If you'd like to know when a new article or chapter for the Step-by-Step Guide is published, send us your email address using the form at the top of the page. You don't need to be a subscriber.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.